Stress Fractures: part 1/4-The what and how

Stress fractures are common amongst endurance athletes. The shear volume of training long-distance runners undertake is a large contributor. We can literally outpace our body’s ability to rebuild our bones after being stressed from activity. There are numerous reasons why this can happen.

What

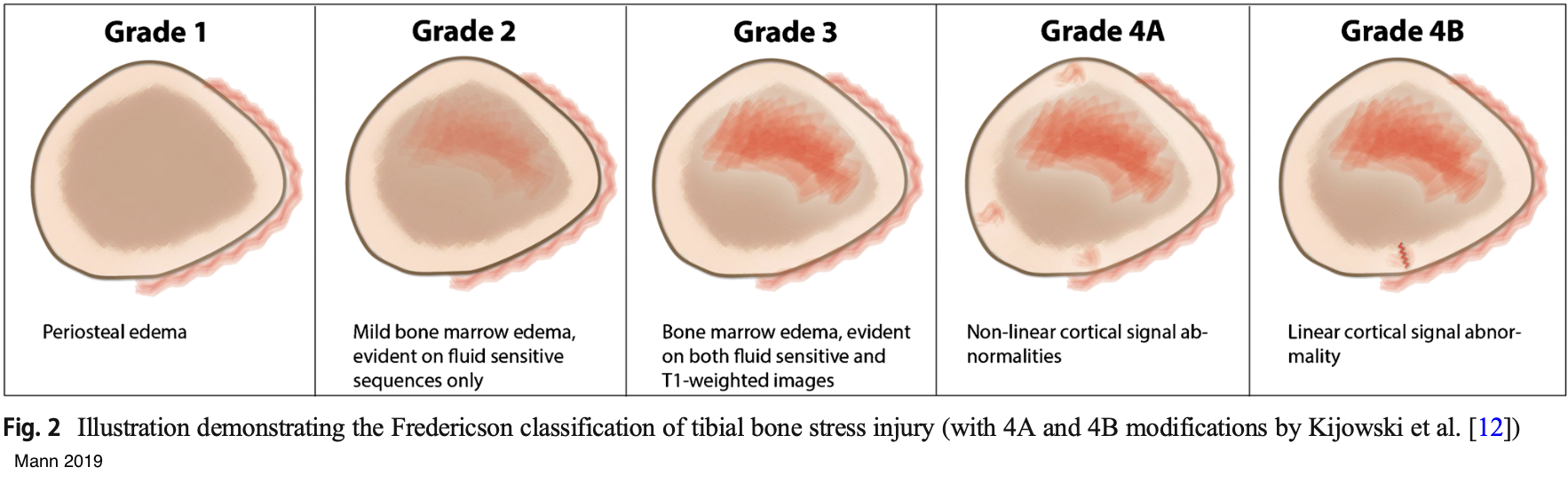

Stress fractures are part of a spectrum of bone injuries ranging from a stress reaction to a full fracture. They are referred to collectively as bone stress injuries (BSIs). The grade of injury will determine the specific diagnosis and degree of severity, which can provide a good lens into appropriate recovery timelines. The injury location will also affect appropriate injury management in the acute stages. Every day our bony tissue replenishes itself, resulting in a complete turnover of bone about every three to four months. (Warden 2014) When our break down of bone outpaces the new bone development, a BSI can develop.

How

This faster rate of breakdown compared to rebuilding can occur for several reasons. There are two primary factors, plus a few secondary factors that can also be relevant in particular cases.

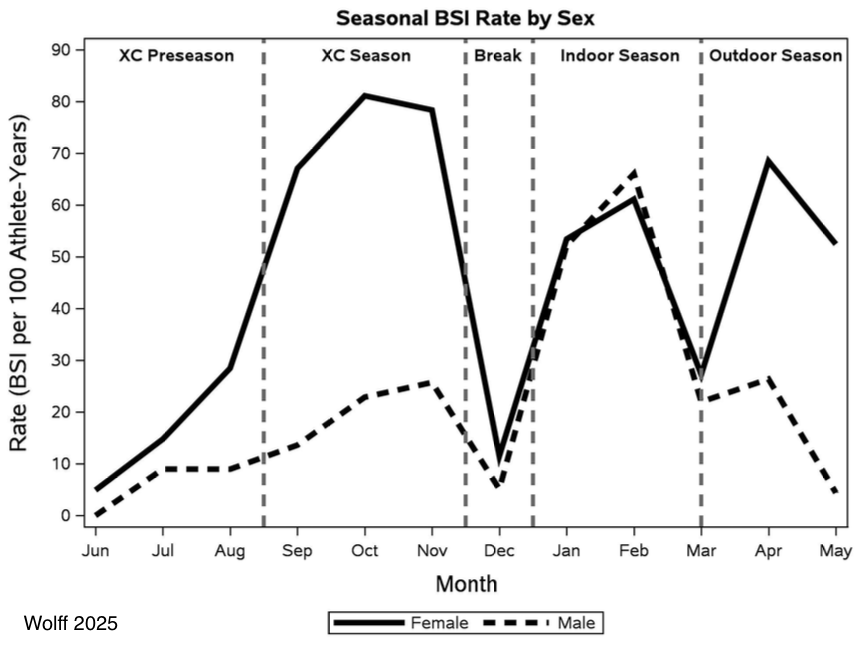

First, our bones adapt to the amount of stress we place upon it. A rapid increase in volume and/or intensity can be too much to recover from in a timely manner. This is why, when going into a training camp or a big training block, you need to go in fresh and be very mindful of what you do afterwards. (Warden 2021) When we look at seasonal patterns of BSI’s in collegiate distance runners, we notice spikes in the development of BSI’s in the early and middle parts of their there competitive seasons (cross country, indoor track, and outdoor track). (Wolff 2025)

Useful guidance on training volume and intensity can be learned from the military, another population with a high incidence of BSI’s. Research tracking the development of stress fractures during the first six months of a recruits’ military career shows that they typically develop in 4 to 10 weeks. (Kardouni 2021) This indicates how long it takes for increased training volume to outpace bone replenishment. I see many situations clinically where the training error begins weeks before the injury onset.

Your fueling and nutrition patterns determine your energy availability (EA), or the difference between your calorie intake and your energy expenditure. In particular, calories from carbohydrates are of interest as they play a vital role in our bone health. Additionally, intake of micronutrients such as calcium and vitamin-D need to be considered. Building a house can serve as a good metaphor here. To build a house, you need both the supplies (specific micro-nutrients) and the contractors (sufficient calories). If you only have one or the other, the house can’t be built.

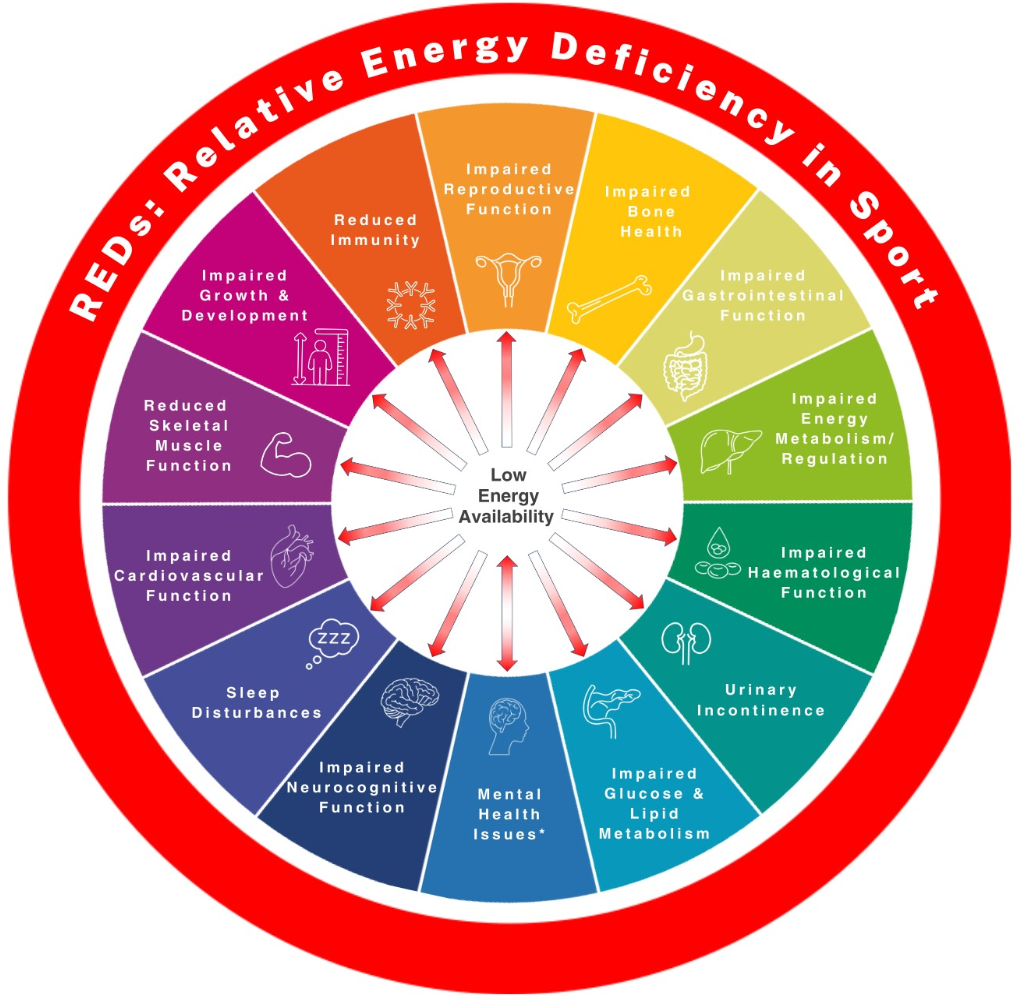

In one study of elite race walkers, a short term restriction in carbohydrates for six days while instead consuming more calories through fat resulted in a decrease in bone formation and increased bone breakdown. This study demonstrates the importance of carbohydrates for bone health in endurance athletes. (Fensham 2022) A still more serious concern arises if we have low energy availability for prolonged periods of many months or more, which results in a condition known as relative energy deficiency in sports or RED-s. (Papageorgiou 2017) Insufficient caloric intake for a long period of time affects a multitude of systems within the body, including the bones, hormones, and GI. It will also negatively affect sleep quality and quantity as well as performance in training.

Missing the mark in our fueling and nutrition for extended periods is often the result of a clinically diagnosed eating disorder such as anorexia or bulimia. However, it can also be unintentional from not increases caloric intake with increases in training volume or intensity. Increased training demands calls for greater nutrition and fueling to enable recovery.

Adopted from the International Olympic Committee Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport Clinical Assessment Tool Version 2

I plan to share more information on this topic in 3 additional articles on secondary factors, preventative strategies, and what recovery and rehab from a BSI looks like. If you need help navigating the intricacies of recovering from a BSI, please don’t hesitate to reach out to us or another trusted professional. I help runners recover from BSI’s and get back to training in Colorado Springs for in-person sessions and across the United States virtually. You can connect with us via phone at (719) 270-3155 or email at runmental@gmail.com. We are also active on Instagram where we frequently post educational material about running rehab and training.

References

S. Warden, I. Davis, et al. Management and prevention of bone stress injuries in long-distance runners. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2014;44(10):749-65.

J. R. Mann, G.G. Wieschhoff, R.Tai, et al. Tibial bone stress injury: diagnostic performance and inter-reader agreement of an abbreviated 5-min magnetic resonance protocol. Skeletal Radiol. 2020;49, 425–434

S. Warden, W. Edwards, et al. Preventing Bone Stress Injuries in Runners with Optimal Workload. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2021 Jun;19(3):298-307.

A. Wolff, L. Kurina, et al. A Descriptive Analysis of the Seasonal Patterns of Bone Stress Injury Incidence in Division I Collegiate Distance Runners. Am J Sports Med. 2025 Mar;53(3):708-716

J. Kardouni, C. McKinnon, et al. Timing of Stress Fractures in Soldiers During the First 6 Career Months: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J Athl Train. 2021 May 11;56(12):1278–1284

N. Fensham, I. Heikura, et al. Short-Term Carbohydrate Restriction Impairs Bone Formation at Rest and During Prolonged Exercise to a Greater Degree than Low Energy Availability. J Bone Miner Res. 2022 Oct;37(10):1915-1925

M. Papageorgiou, E. Dolan, et al. Reduced energy availability: implications for bone health in physically active populations. Eur J Nutr. 2017 Jul 18;57(3):847–859

International Olympic Committee Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport Clinical Assessment Tool Version 2